NARRATIVES

HOLY COMMUNION

North India

On a dark full moon night, the light shines forth from the Golden Temple. The mysterious source of dazzle draws gazes, thoughts and prayers, bewitching the scattered crowd of pilgrims. Seated in the front row, privileged before others, Sardars surround the “pool of immortal nectar,” forming a continuous line of reciters. The words they utter can barely be heard, but closed eyes testify their sacred character. A few feet behind them, under the archways, families have gathered to enjoy a blessed rest. Unaware of the holiness of the place, children simply play around loudly and cheerfully. Their elder brothers focus their attention on religious books, although they temporarily interrupt their reading to answer phone calls and messages, intrusive reminders of the material world. Behind them, many have already fallen into a deep sleep, seemingly unaware of the dazzling light. Despite the bright outside world, their inner self lies down peacefully. Believers might be the ones who contemplate the sweetest of all dreams.

As I step outside the Amritsar Shatabdi train, Roxanne welcomes me with joy and happily grants my wish to be immediately taken to Harmandir Sahib, the “abode of God.” I have come to Punjab for her wedding with Ajaypal, the Sikh who won her heart during their studies in New Orleans. This incredible romance is the perfect excuse for my first trip to the subcontinent. After the four days celebration of an authentic Indian wedding, I will travel for three weeks throughout the Himalayas, guided by kamalan, the Indian company she recommended for our small group of high school friends.

For now, my urge cannot wait: I have to see the Golden Temple.

A deep silence reigns over the religious complex, contrasting with our constant chattering on the way. As I stand in awe of the monumental beauty before our eyes, we start our clockwise walk around the lake. An endless cloth shows the way to our bare feet. Roxanne murmurs respectfully and tells me about the history of this Gurdwara –the place of worship for Sikhs– built at the end of the 16th century and covered in gold during the 19th. As we enter the temple, we witness something most unexpected: hundreds of people have gathered to pray, despite the late hour in the night. Many sit cross-legged on the floor, as they listen to the religious singing that punctuates the rhythm of the harmonium and drums. The inside magnificence of this architectural masterpiece, covered in marble, gold and precious stones, overwhelms the unaware. But we go through too quickly, unable to grasp the substance of the night’s prayers. As I am offered sweet prasada on my way out, I make it a point to come back no later than the following day.

It is 11 a.m. when I remove my shoes and cover my head in a now familiar gesture. I have left my friend to the last preparations for her wedding, and I return alone to the Golden Temple. “Alone” feels somehow an inadequate term, while surrounded by devotees, who pray, bathe and read, welcoming the foreigner that I am with the most natural warmth. As I start all over again my clockwise path, I stop around 9, attracted by a crowd unnoticed the previous night. In the inner courtyard, people are peeling garlic; thousands of cloves lie on the floor. The task of cooking for the community is extremely ordered. Each hand, every gesture, has a purpose.

A large jar contains tons of chopped onions, whose pinkish white contrasts with the brown of a forgotten rolling pin. For a minute, I wonder what kind of religious practice puts garlic and onions at its core. In a large and dark shed, people sit in line, facing their thalis as they are served daal and chapatis at will. The silence is religious.

Volunteers go back and forth, carrying buckets of lentils, baskets of rotis and teapots of warm chai. I follow them into the anteroom, a few square feet between the kitchen and the hall, where food is stockpiled before being served. Two men with turbans, a faraway look in their eyes, watch over an army of whole-wheat bread.

One has to cross the street to reach the back kitchen, where saucepans rise above the height of a twelve-year-old. The smell tickling my nostrils is exquisite. Meeting my hungry gaze, a compassionate woman hands me a warm chapati with a smile. She might well recognize her elder son in me. I could stay here all day, rocked by the cooks’ conversations and the sizzling of their fire. In the nearby room, a machine kneads the dough, in another, daal and chai simmer. Leaving the hot atmosphere of the kitchen, I come across a new hive of activity, different in nature. As the meal ends, water succeeds to fire.

Volunteers remain silent as they rhythmically carry out their duty. On the main stairs, a line of colourful turbans has formed to collect the dishes. In front, two men are in charge of recovering forks that are washed separately. As I get closer to one of them, I hear a piece of indistinct music. I listen more carefully, trying to forget the clanging of the dishes when suddenly it strikes me. His song resembles the one from last evening in the Gurdwara. The old man under the indigo turban is praying. In the land of Hinduism, determined by strict food rules, Sikhism proposes an egalitarian alternative: everyone can serve and everyone can be served. Volunteers and pilgrims have not only gathered for a meal, but for a unique kind of “holy communion”.

Paradise Must Be Gained

Far from the maddening crowd, out of the beaten track, a journey to the Andaman brings the traveller to the end of...

Narrative • South India

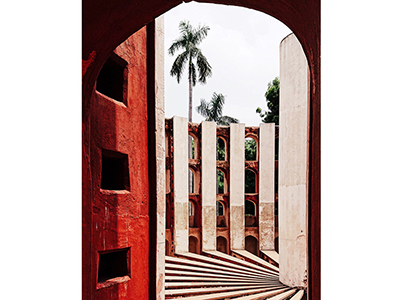

The Life in Architecture

What we build is influenced by and is a reflection of the times we live in. The roof that is built, the colour painted, the materials used...

Narrative • North India

In Search of Artisans

Delve into our journey with Hole & Corner across Rajasthan where we explored handicraft and textile traditions in this land of plenty...

Behind-The-Scenes • North India

Kingdoms of Old

This journey traces heritage through the remnants of the dynasties that ruled Madhya Pradesh from ancient times till the present...

Bespoke Journey • West India

Taj Rambagh Palace

Hailed as the stunning ‘Jewel of Jaipur’, the Taj Rambagh is a palace of transitions. It was built...

Hotel Guide • North India

Rising With The Sun in Nimaj

Indians wake up early, often as the sun rises, to pray to the gods for a favourable day and enjoy the few hours where there is no need to hide in the shade...