NARRATIVES

AT THE EDGE OF THE DESERT

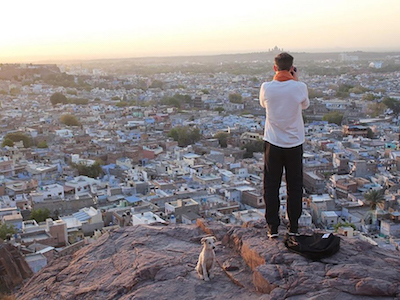

North India

Sand easily overtakes the careless traveller. Grain by grain, it squeezes slowly between tight lips, it threads its way through half-open shoes, and it catches at freshly washed hair. It can turn a strong eyelid into an inconvenient strainer. No notice board warns you beforehand, with a stock expression such as those sometimes found between official frontiers, 'You are now entering the Thar Desert.' The soil lacks a strict magenta line to mark the boundaries between the before and the after, between nature and man. One never finds oneself at the edge of the desert, but progressively dives into it, like into a deep ocean.

Nothing like the legendary African Sahara where earth completely fades away under the dominant sand dunes. Yet the body feels early symptoms; the skin asks for water and the body does not respond to the mind anymore, an ancestral oath of allegiance tying it to the land.

I turn my head, look at the others, and wonder. Bare-chested children walk without shoes on the mud floor; men sit quietly under the shade, no motion indicating any discomfort. If a beetle lands loudly on one of their shoulders, they don’t even seem to notice.

Far away from Western capitals, skyscrapers and pollution, the desert offers a place of harmony between humanity and nature. In the Thar, as described by the Greek poet Kimon Friar, speaking about his own country, there is "a sensuous acceptance of the body as it is, without remorse or guilt". The flesh acknowledges its blood ties with other species. There is only one option: to let go.

The name 'Marwar', which refers to the region sprawling around Jodhpur, means, according to some, 'the land of death' or, as explained by others, 'the land defended by the desert'. The fauna that blossoms in every nook and cranny confirm the latter interpretation. Local hotels organise excursions into the arid countryside so that visitors might look at wild cats and foxes, take pictures of stately black-buck antelopes, and admire colourful wild peacocks, India's national bird.

Bishnoi communities carefully protect them according to the twenty-nine precepts of their faith. Men dressed in white, nature’s volunteers, comb through the region on motorbikes looking for any threat to biodiversity. The monsoon relieves the desert of its orange and dyes it green. The Prosopis cinerarium, commonly named Khejri, stands erect. The shade of its leaves welcomes the pilgrim on a long journey to the temple, the woman walking to the nearby well or children stopping bicycles for some well-deserved refreshment. Locals rejoice at the sap flowing through the tree’s trunk and branches. The Khejri offers thin and delicious peas in exchange for this attentive care.

At scattered watering places, cattle come together: buffalo, sheep, goats, and sometimes, camels and donkeys. They give their backs, their wool, and their milk to the brave people who call the desert home. Depending on agriculture and animal husbandry, villagers have grown familiar with the untameable nature that surrounds them. They build mud houses. Often, they live as nomads, walking the cattle to Gujarat in the dry season and carrying their folk culture, music and dances with them. Modern men from the cities have come and tried to change nature. They have built canals to bring water from the Himalayas down to Jodhpur. Water means crops. Water means more cattle. Water means better living conditions. The vast desert stands still but with an occasional flutter, to call out to the cities to return its people, to the ones who will return and never leave it.

In Anticipation of Petrichor

Rain is happiness, rain is melancholy, rain is nostalgia. For Indians, it’s more than just these; it is a part of life...

Narrative

Of Virginia Woolf, Cereal and Kamalan

Always interested in exploring the fluid relationship between art, literature and travel, we were instantly drawn to the aesthetics and...

Narrative • North India

A Wondrous Moonland

A journey that takes one through the surreal mountainscapes and the unique lifestyles of the Ladakh region...

Bespoke Journey • North India

Journey of A Faith

A journey tracing the history and tenets of Sikhism, a religion born in the state of Punjab...

Bespoke Journey • North India

Taj Rambagh Palace

Hailed as the stunning ‘Jewel of Jaipur’, the Taj Rambagh is a palace of transitions. It was built...

Hotel Guide • North India

Seize the Place

Ahmedabad is white and yellow under winter’s sun, melting houses banally spread beyond her sight. Yet one more sprawling city...